- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

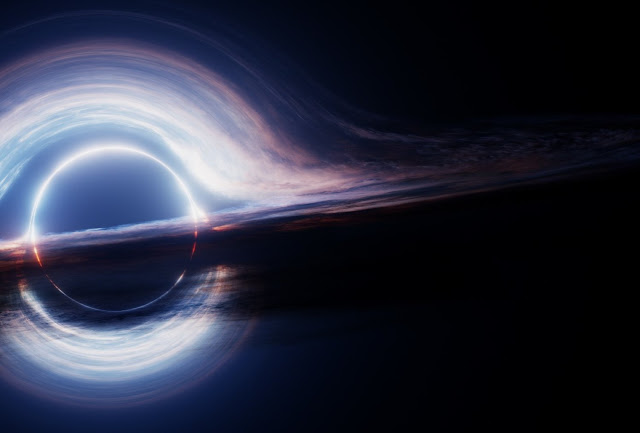

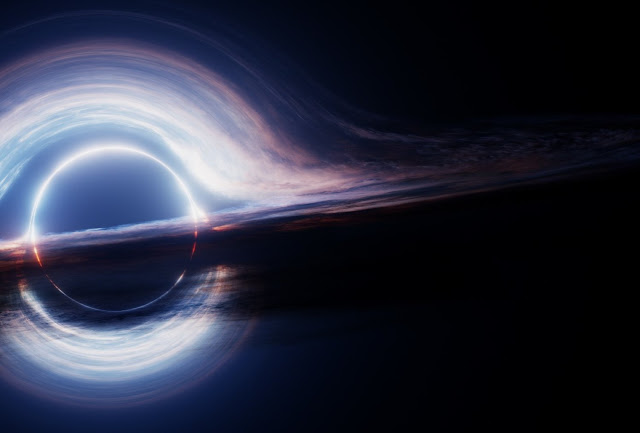

Japan deployed a ground-breaking black-hole tracking satellite, only to lose control of it nearly immediately due to unusual conditions. We can now see what Hitomi did before it died. When JAXA launched Hitomi in February of this year, scientists were ecstatic about what the black hole monitoring satellite would reveal about the universe's mysteries. It had barely been a month up there when something went wrong. The satellite spun out of control due to a succession of tragic occurrences caused by both human error and software problems. Despite repeated attempts to restore control, Hitomi continued to spin and launch debris into space. JAXA eventually declared that the $273 million satellite was irreparable. However, when Hitomi died, researchers also disclosed that they had scraped a small amount of data from the satellite and would be documenting it in subsequent studies. Some of that data is now available in a new report published in Nature, which includes Hitomi's final observation. It has some intriguing implications for our understanding of the role of black holes in galaxy formation. Hitomi's final observations were of the Perseus Cluster, a 240 million light-year-apart galaxy cluster with a supermassive black hole at its heart. The satellite obtained this view of the galaxy and measured its x-ray activity: Researchers expected to detect a flurry of activity in the cluster's core, but Hitomi's final x-ray measurements revealed virtually little. “The intracluster gas is quieter than expected,” co-author Andrew Fabian of Cambridge University told Gizmodo. “We expected that the level would be higher based on the activity of the central galaxy.” But the finding isn’t just a surprising oasis of calm in a turbulent galaxy. It also gives us insight into just what role black holes play in how galaxies do—or don’t—form. “Black holes very effectively control the growth rate of galaxies.” “The surprise is that it turns out that the energy being pumped out of the black hole is being very efficiently absorbed,” co-author Brian McNamara of the University of Waterloo told Gizmodo. “This hot gas that we’re looking at with Hitomi is the stuff of the future, it’s the gas out of which galaxies form. There is much more of this hot gas than there are stars in the galaxy, or there’s more stuff that wasn’t made into galaxies than that was.” That means that nearby black holes play a big role in the eventual size of a galaxy. “What it shows is that black holes very effectively control the growth rate of galaxies,” said McNamara. Of course, the finding underscores how little we still know about the role of black holes in galaxy formation. It also gives us a tantalizing look at how much promise the satellite held before it was lost. The loss is even bigger because Hitomi marked what researchers hoped would be the end of a long-standing struggle to finally stick an x-ray microcalorimeter—a device used to take incredibly precise measurements of the energy in x-rays—into space. The findings in today’s study were based on just a very small sample of data researchers were able to get from Hitomi’s microcalorimeter before it was lost, and it already has them speculating over what could have been. “The measurements on the Perseus Cluster showed the potential of the Hitomi x-ray microcalorimeter to transform our understanding of the velocities of hot gas throughout the Universe,” Fabian said. Before Hitomi, there were two other attempts to send a microcalorimeter into space—and both ended in strange accidents. In 2000, a rocket mission that would have sent the first microcalorimeter into space exploded upon launch. In 2005, a microcalorimeter actually made it into space, but was destroyed by a coolant leak. It wasn’t until 2016 with Hitomi that a microcalorimeter was successfully launched long enough to take take measurements—only to be lost along with the entire satellite shortly after. “It’s a huge loss, because just from that glimpse we can see the wonderful science that might have been over the next five years,” said McNamara. “We had a whole landscape of planned observations and that first glimpse we got with the detector shows the richness of what we could find. There were surely discoveries that would have been made when we opened that window.” Still, even though Hitomi’s microcalorimeter and the observations it would have made are lost, there are other opportunities to send another microcalorimeter into space aboard some other upcoming mission.“There loss, but there’s also hope, we never give up,” McNamera said. “We’re hoping we can still get one there.”

Comments

Post a Comment