- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

The search for planets in distant solar systems has taken one more step forward with the entrance of a new planet-detecting tool led by a Stanford physicist. The Gemini Planet Imager (GPI) has set a great standard for itself. The very first image snapped by its camera created the best-ever direct photo of a planet in a distant solar system.

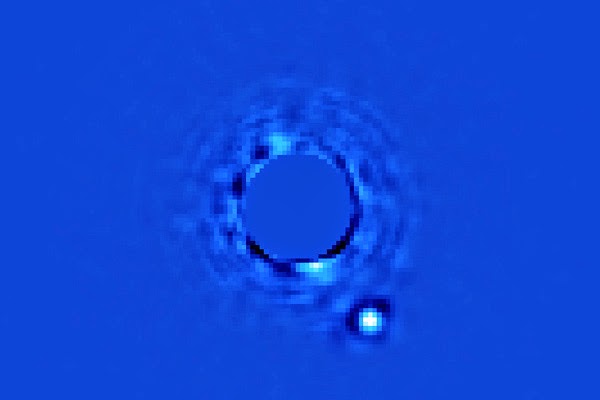

The bright white dot is the planet Beta Pictoris b. The bright star Beta Pictoris is hidden behind a cover at the centre of the image. Image processing by Christian Marois, NRC Canada

The planet is known as Beta Pictoris b. The photo of Beta Pictoris b is more inspiring because it is more than 63 light-years from Planet Earth. Beta Pictoris b is observable in a single 60-second exposure and with previous instruments used for detecting exoplanets, it would have taken over an hour. The collective GPI data set exposed vital details of the planet’s trajectory and axis and its bond to a close asteroid belt.

These vital details also let Macintosh’s team forecast that in 2017 the planet may “transit”, pass right in front of its parental star. Though the Kepler mission has revealed thousands of transiting planets but none has been openly seen.

Not a lot of planets have been directly imaged since construction initiated in 2004 on the GPI, a ground-based tool at the Gemini South Telescope near Chile. The previous group of adaptive optics, still, was only sensitive enough to detect planets that were considerably larger than Jupiter and only those planets which were as far away from their parent stars such as Saturn or Neptune is from our Sun.

The GPI’s innovative optics are adjusted to discover faded planets circling very bright stars. This makes it conceivable to spot Jupiter-sized planets orbiting closer to stars that are a lot like our own. Macintosh estimates that his team might be able to detect and describe 20 to 50 planets.

Macintosh said, “To some extent, this is really the old looking-for-the-keys-under-the-searchlight joke. We look around bright nearby stars because we need the stars to be bright for GPI to work. But stars that are bright and close let you get lots more photons from the star and planet, and you can do a better job of understanding the planet.”

The sensitive camera will be capable enough to accurately measure the planet’s temperature and its chemical configuration, which will let computer models of the atmosphere and weather become a lot more accurate. This information could then produce clues as to how the planet was made. Unluckily, the GPI might not be able to detect Earth-like planets as they’re too small and they won’t reflect much light to be spotted.

The discovery was published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Comments

Post a Comment