- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

- Get link

- X

- Other Apps

Four Jupiter-mass exoplanets dance around their parent star in a stunning new timelapse collected over a dozen years.

The aim of the newly released video is to make the long orbits of these massive exoplanets more recognizable to a wide audience, Northwestern University astrophysicist Jason Wang said in a statement.

"This video shows planets moving on a human time scale. I hope it enables people to enjoy something wondrous," said Wang. In real life, the planet nearest the star HR8799 takes 45 years to make a single circuit. The world farthest away would take half a millennium (500 years) to go around the star once.

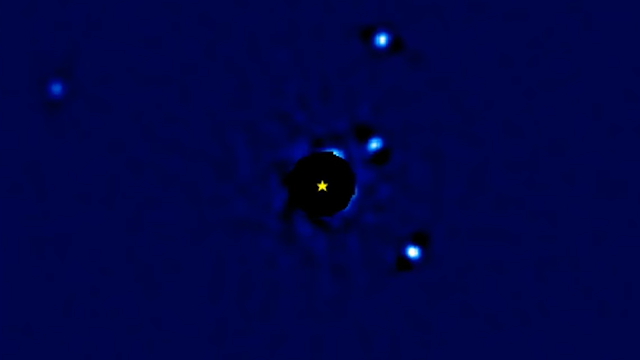

A timelapse animation of the four exoplanets "dancing" around the star HR8799. (Image credit: Jason Wang/Northwestern University)

HR8799 is 1.5 times more massive than our sun and lies roughly 133 light-years from Earth in the constellation Pegasus. (By comparison, the closest star system to us, Alpha Centauri, is a bit more than 4 light-years away.)

While a bit more massive than our sun, HR8799 is much more luminous: it has five times the intrinsic brightness of Earth's start. HR8799 is also very young at just 30 million years, compared with our midlife sun, which is 4.5 billion years old.

Three planets in the HR8799 system. The planets, thought to be gas giants more massive than Jupiter, were first imaged in 2008 and are shown here in a vortex coronagraph image. (Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/Palomar Observatory)

HR8799 was the first star system ever to have its planets directly imaged, which was accomplished and announced in November 2008. The new timelapse uses footage from the W. M. Keck Observatory atop Maunakea in Hawaii.

Keck has great advantages for astronomy: adaptive optics to compensate for the blurring effects of Earth's atmosphere, and a coronagraph that blocks the light from the parent star, allowing the reflected-light "fireflies" (planets) to shine through.

Wang and his colleagues created one timelapse after using seven years of periodic observations. The newly released timelapse is an updated version, with 12 years of observations from when Wang's team had access to the telescope.

"There’s nothing to be gained scientifically from watching the orbiting systems in a timelapse video, but it helps others appreciate what we’re studying," Wang said. "It can be difficult to explain the nuances of science with words. But showing science in action helps others understand its importance."

Comments

Post a Comment